I have seen a few cases lately whereby owners have noticed a change in their dog’s coat. Some owners are really aware of coat changes whereas other people might not be aware or know what to look out for, hence this blog post!

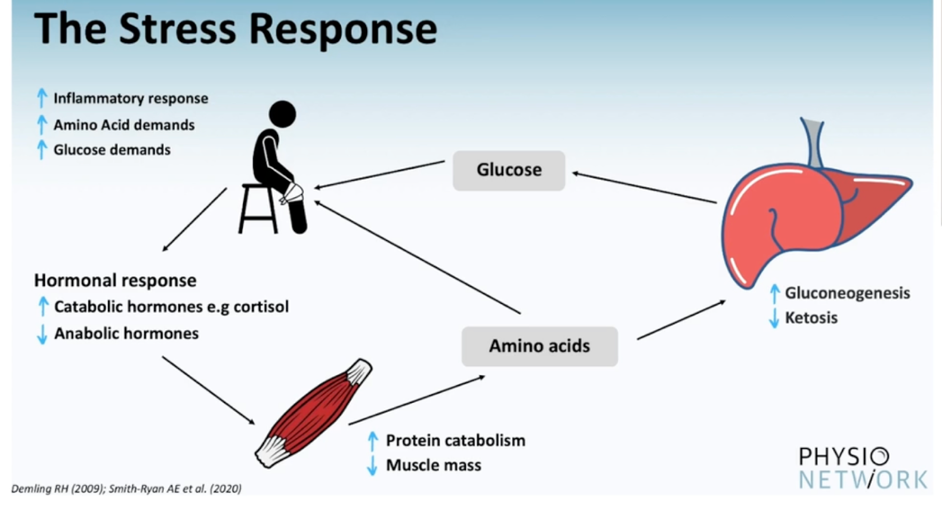

The reason noticing coat changes is useful is because it can indicate a dysfunction. It could be due to an injury or a change in the musculoskeletal system such as muscles. Or it could be due to a non-musculoskeletal condition such as thyroid issues, intake of dietary fats, thermoregulation after exercise or stress. In this blog I will focus on the musculoskeletal reasons coat changes might happen.

Firstly, what are you looking for? Well it can be located to a small area where the fur might stand up slightly higher, the fur can curl or ‘swirl’ in the area or it might look unusually flat. It can also be global whereby the fur along your dog’s spine is roughened, almost looking like a ridge. If you usually keep an eye on your dog’s coat the change in hair is usually obvious but I have seen many cases whereby owners have not noticed at all. It usually then stems the questions, ‘Is that normal for your dog? ‘Has it been there before?’.

The reason fur changes can occur from a physio perspective can be age, mainly because the older the dog the more cellular atrophy there is within the skin. The skin also loses elasticity which can cause coat changes.

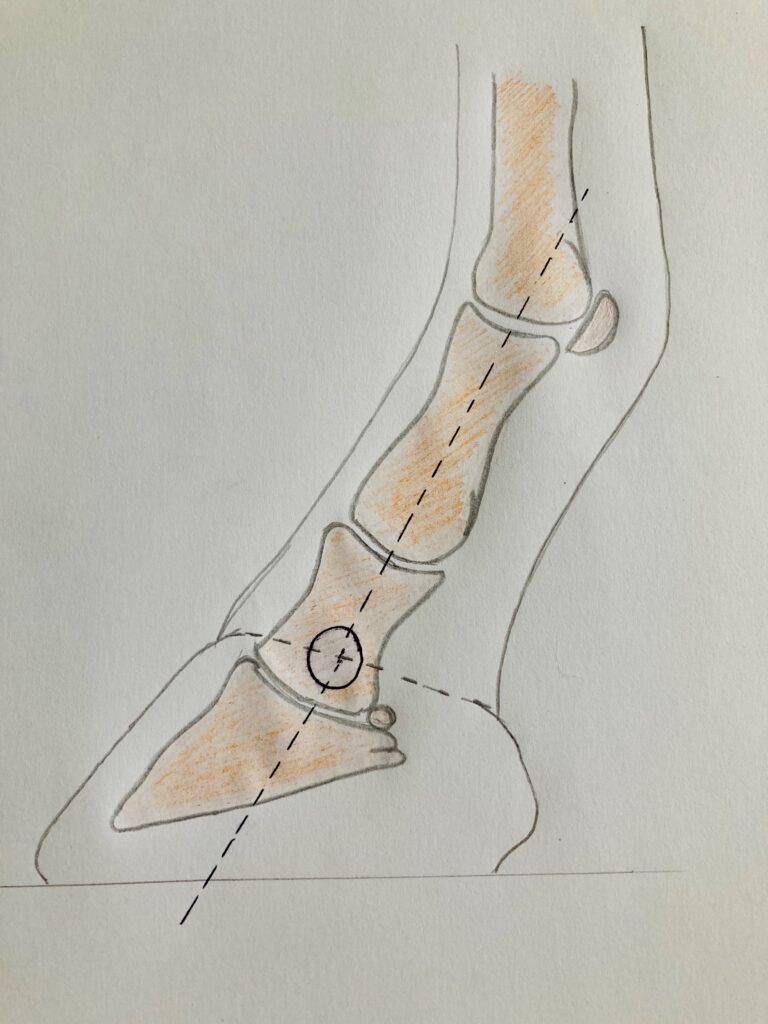

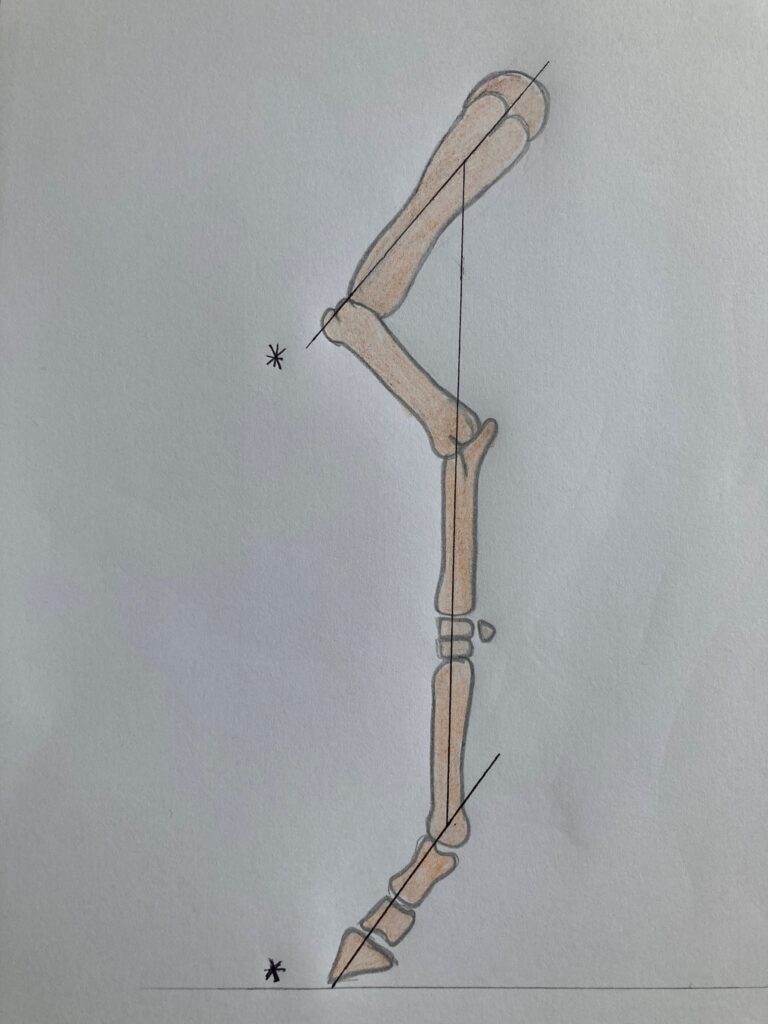

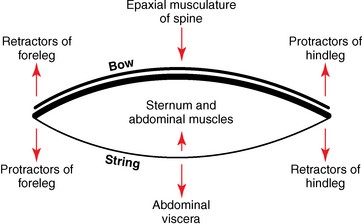

Now if your dog is young with new coat changes then that can be due to muscular reasons. Taut muscle fibres otherwise known as trigger points can affect the muscle elasticity and pliability which can cause fur changes. Myofascial restriction is another component to consider. Myofascia is the connective tissue which encases muscles and organs. Myofascia should allow muscles to contract and relax but if this is taut then resistance can occur and muscles can get tight. In this case potentially leading to changes in fur.

The picture of the left shows the fur deviating to the left and is slightly raised. On the other picture you can also see some deviation to the right with the arrow on the right. Musculoskeletally the Trapezius muscle group , Rhomboids and part of their superficial stabilisers sit there. Treatment involved releasing these muscle groups to see if the fur changed.

Following treatment the above picture shows a change from the first two photos. The main area of focus has improved because the fur is flattened with less deviation. There are some fur changes higher up however on the left which you can see by the arrow. This is an example of how the connective tissue (fascia) is one large continuous structure. In this case further treatment was needed and the origin of the problem was found to be mild elbow dysplasia. So coat changes not only help understand what areas need treating but also helps piece the wider puzzle together.

Other case examples more recently include;

- A 8 year old working Labrador with a ‘ridge of hair’ appear just in-front of the hip and into its quadricep muscle group.

- A 8 year old Collie with a small patch of hair just left of its mid thoracic spine standing up on end.

- A 6year old Jack Russel with a flattened fur behind the left scapula

So the best thing to do is to keep an eye on your dogs coat, just as we look for lumps and bumps it would be useful to do this regularly with your dog and their coat. Taking pictures is one way you can do this or keeping a diary to get a good history is always useful. I hope you found this useful, if you have any questions or comments please do get in touch via the contact page.